This week we’re talking about the power of voice. As always, you can skip to the bottom for the monster of the week, the Shryklops. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, please share or forward it to someone you think would also like it.

If someone tells you they lost their voice, they’re lying.

The Voice of AI

I’m not bullish on AI but I do think it’s interesting, occasionally useful, and often wildly oversold. Recently I came across a few examples of AI slipping into video games in ways that aren’t hypothetical. They got me thinking about the real ways AI is will show up not just in games, but software overall. I expect AI to affect content generation, gameplay mechanics, and how people interact with software through their voice.

The thing that that I was reminded most of was my own early work in video games. Especially on SOCOM: U.S. Navy Seals, the first game I shipped over twenty years ago.

When I was a Young'un

Back in 2002, SOCOM: U.S. Navy SEALs launched with a novelty feature. The box included a headset and microphone so you could give orders to your computer controlled teammates. You weren’t doing anything you couldn’t already do through the in-game menus. Either the menus or your voice could order your teammates to “Move up,” “Hold position,” “Regroup,” etc. However, the act of saying the words out loud made the game more immersive. Players could feel like an officer issuing commands instead of a player clicking through menus.

Every piece of SOCOM was handcrafted. The team at Zipper Interactive was maybe two dozen people, including the mailman. A decade later, when the final SOCOM game was released, the studio had more than a hundred people. The scale of the work had increased, but the process stayed the same. You still had to write, record, animate, and tune every last detail.

Excessive Grunting

We needed to record a decent amount of dialog for that first game. Twenty-six voice actors contributed, more than twice as many software engineers who worked on the project. Designers wrote variations of nearly every line. Actors recorded variations of each line so the game would have variety. Audio engineers sifted, mixed and tuned everything to sound cohesive. The work was meticulous and time consuming. We probably would have used more voice actors if we could have, but every additional line meant more actors, more studio hours, more engineering, and more iteration.

Compare that experience to what we’re seeing now. The game ARC Raiders recently caught attention, and criticism, for using AI to generate a some of its dialogue. The decision for that team was practical. They wanted game characters to be able to name hundreds or even thousands of in-game items. Bringing actors back into the studio every time a new batch of gear was added just wasn’t feasible. So the developers worked with their voice actors, paid them, and got consent to use their performances to tune a text-to-speech engine that could fill in the small, repetitive variations. The criticism leveled at them was that they were using AI to take away jobs from voice actors.

AI is taking those jobs, for sure. The developers could have spent more time and paid more to get all the dialog from real humans instead of using a computer to generate it. What ARC Raiders did instead, was have the voice actors set the tone and personality for the characters, but the endless “small” performances (a dozen variations of grunting, naming a dozen different metals, voicing the names of a hundred different pistols) are handled by the machine. The longer speeches, emotional beats, focused performances still rely on human actors, and probably will in all games for a long time to come. What's changed is the amount of booth time spent recording minor variations that few were consciously appreciating anyway.

Give me 10 different takes on the phrase, “Ow, it hurts!”

The same kind of shift will eventually touch other parts of game creation. Technically minded artists still hold an advantage because in-game assets require a lot of fiddly precision work like UV mapping, mesh optimization, and fine-tuning animations. AI isn’t great at that (yet). But concept art and writing background details are already being made more efficient by AI tools. Music and sound design are squarely in AI’s sights, too. These areas of the creative process are more forgiving to the imperfections that AI naturally introduces. I expect a lot of design work to get picked up by AI as well. Game designers who spend all day churning out small level variants, quest snippets, and filler dialogue will feel the pressure. If your job description at a game company requires careful, technical exactness, AI will probably help you more than replace you. If your contribution involves lots of little non-technical variations and the quality bar is subjective, you're probably feeling a little chilly standing in AI’s shadow.

You Got AI In My Gameplay

Gameplay is also shifting. SOCOM’s enemies and teammates were driven by an intricate series of state machines, heuristics, and randomness. We had to program explicit instructions for everything they could do: move closer if the player is far, retreat if they’re too close, hold position with a certain weapon, surrender if alone and injured. The system depended on designers and programmers layering behaviors until they felt believable and fun.

Ubisoft’s recent Teammates tech demo shows a different approach. Its AI driven companions don't necessarily behave much differently from the SOCOM teammates we built two decades ago. They move, flank, shoot, take cover, and respond to the world around them. Under the hood, the way those decisions gets made has changed. Instead of branching logic trees and state machines, GenAI evaluates the situation and decides the next set of actions from the possible behaviors.

How to determine what game knowledge needs to be passed to the AI is still programmed the old fashioned way. Navigation systems and animations still need to be created. The AI isn’t inventing new moves out of thin air. But by handing the “what should I do next?” step to an AI model instead of a rigid state machine, Ubisoft can be a little fuzzier, a little more flexible, and possibly a bit faster in development.

The AI doesn’t make the characters it controls smarter or able to do things that weren't anticipated by the developers. It just changes how the available options are evaluated and how to arrive at a decision on what to do next. In practice, that means fewer people writing sprawling behavior trees and more people orchestrating things at a higher level.

Using Your Inside Voice

The biggest shift from a consumer perspective may be in how we interact with games and software. Voice control has existed for years, but it’s typically a one to one mapping of voice to user interface: speak the name of a button, and the system “clicks” it. SOCOM’s command system was essentially the same thing with military phrasing. Quirky and fun, but not a revolution.

The command menu in SOCOM: U.S. Navy Seals

The new wave of voice interfaces hints at something more natural. Ubisoft’s demo suggests a future where you can speak to a game, or really any piece of software, the way you speak to another person. Not a list of commands, but intent. Things like “Tell the squad to flank left and wait for me," or “Increase the brightness and adjust for color blindness,” or “I'm deaf. Turn on all the right accessibility options for me.”

While voice assistants like Alexa have been inching toward this for years, seeing it embedded within a complex, real-time system like a game says a lot about what’s now possible across software in general. For many people who can’t use a mouse or keyboard, this shift could remove barriers that have existed for decades and make people more confident in their ability to use and enjoy software.

Applying to Accessibility

AI-driven interfaces do raise concerns about accessibility. Historically, it’s taken an incredibly long time for new technologies to become fully accessible. Television didn’t have universal captioning until 2006, eighty years after television was invented. Some people hope AI might accelerate accessibility by giving users a more adaptive, intent-driven way to interact with the digital world, just like we're seeing in the Teammates demo.

It's natural to worry this will repeat old mistakes. "Accessibility overlays" promised to make websites accessible and rarely did. They created separate, inferior experiences. Inaccessible design can't be made accessible with grafted on technology. AI risks the same kind of “separate but automated” path if companies treat it as a solution that excuses them from building things accessibly in the first place.

There’s another concerning trend beginning to bubble up. People are starting to talk about how accessible software can be easier for AI to manipulate. If AI systems start depending on ARIA roles, semantic HTML, and other accessibility markers to understand interfaces, the temptation to distort those markers to make software more usable by AI creeps in. In the same way search engine optimization has distorted product descriptions in online shopping, perfectly good accessibility metadata might get hijacked for AI optimization, making things worse for the very people it was built to help.

An example of a long product title designed for machines and not humans.

Building user interfaces to work with voice control systems involves many of the same techniques as making software accessible to other assistive technologies. Element labels need to be short and unique to make it easier to understand and say them. You should try to reduce the number of elements to make navigation and comprehension more efficient. If software developers start ignoring the human users of assistive technology in favor of optimizing these aspects for AI use, we’ll end up with a lot more barriers for people with disabilities.

Evolution Not Revolution

None of what we're seeing makes AI a magic hammer to drive all nails. I still don't think AI is going to completely transform the software industry, games included. It's more subtle than that. AI is sliding into the production processes that have always been labor-intensive and brittle. It’s optimizing the jobs full of small tasks that humans performed largely out of necessity rather than creative choice.

In content generation, it’s becoming the source of small variations that were once tediously hand crafted. In gameplay, it’s nudging aside the rules based systems we used for decades and replacing them with something more dynamic and adaptive. In control schemes, it’s inching us toward software that understands intent instead of demanding memorized commands.

These aren’t headline grabbing revolutions. They’re more like quiet edits to how games, and software more broadly, might be made. These edits could make our tools more flexible and our worlds more accessible. But if we’re not careful, they could give us a more fragmented, less human digital landscape.

Relevant Links

For more info, check out some of the links below

Ubisoft Teammates Demo - A great writeup by someone who was hands-on with the demo.

ARC Raiders using AI in its games - A good writeup on the use of AI to generate content for the game ARC Raiders.

SOCOM: U.S. Navy Seals Credits - I’m in there!

Bulletproofing yourself against AI - My thoughts on how to keep AI from taking your job.

What I’m Hyping Right Now

The Navigating Fox is a rich tale set in a world of talking animals and humans. The world has a lively texture and feels bigger than its short 160 pages.

There’s a lot of world-building, but it never feels heavy. The setting opens up naturally as we follow Quintus, the world’s only talking fox, whose journey is as much internal as it is geographical. He’s pulled between a desire for revenge and a deeper hunger to understand his origins. That tension gives the story emotional weight.

For such a brief read, it’s remarkably deep: playful on the surface, thoughtful underneath, and utterly memorable.

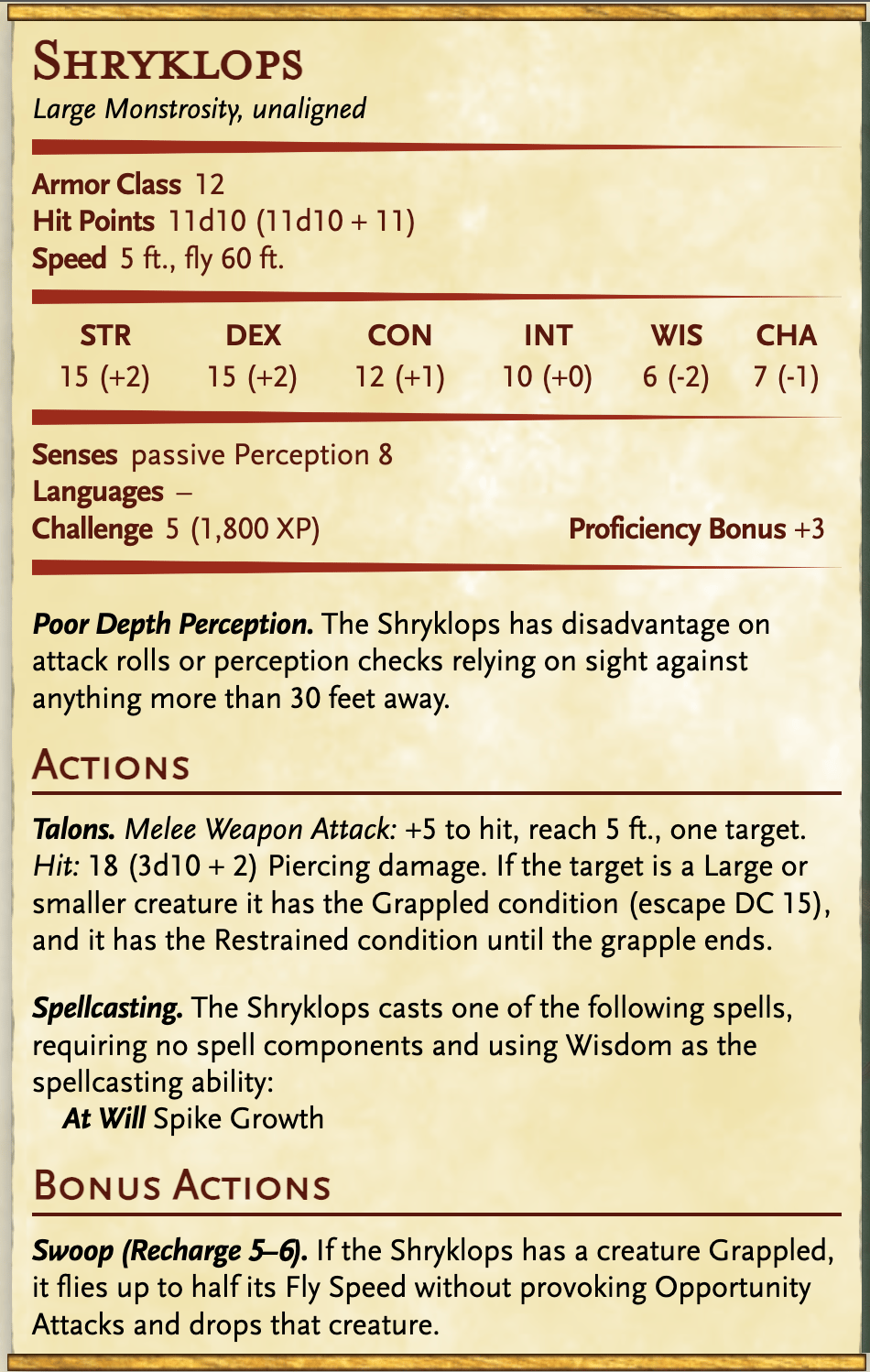

Shryklops

The Shryklops is a monstrously oversized Shrike twisted by magic, its single, unblinking eye gleaming like a polished opal. Created by the eccentric antiquarian Thaloran Vist, the creature was meant to be an obedient fetch-beast. Something that could locate lost artifacts, snatch them up, and deliver them safely home. Instead, Thaloran’s spellwork fused avian instinct with arcane predation. Now the Shryklops hunts the high forests and cliff edges, silently gliding until it spots movement below. With impossible strength, it plucks travelers off the ground and drops them screaming into the barbed, living briars that writhe and tighten around whatever falls into them.

As always, you can find more on the Shryklops for free over on Patreon.

Some links on this site are affiliate links that may give me a kickback if you buy something. There’s never an extra charge to you.